Why are Workers so Scared for the Future?

In both the US and the UK, workers have been left out of the post-pandemic economic bonanza - and they know things are about to get worse.

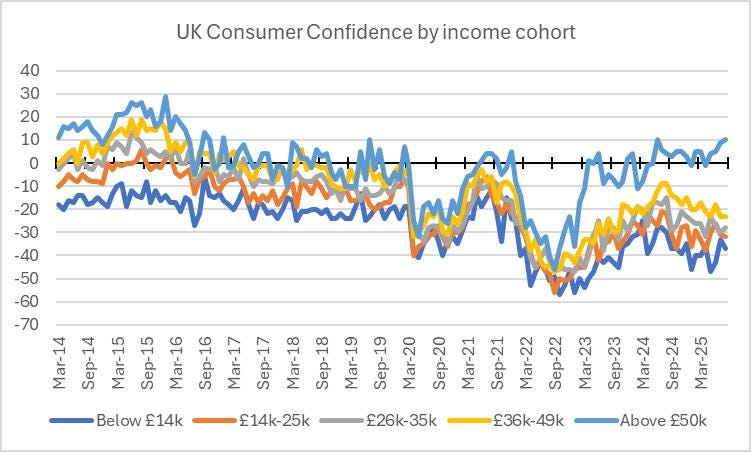

A few weeks ago, an acquaintance who works in finance sent me this graph, which shows consumer confidence in the UK by income cohort.

The first thing you’ll notice is the sharp upwards trend in consumer confidence for those earning over £50,000 since 2022 (the light blue line). All the other income cohorts saw a similar U-shaped patter in consumer confidence during the pandemic. But since the start of 2024, the confidence of those with incomes under £50,000 per year has been trending down, while the confidence of those earning over £50,000 per year has been trending up.

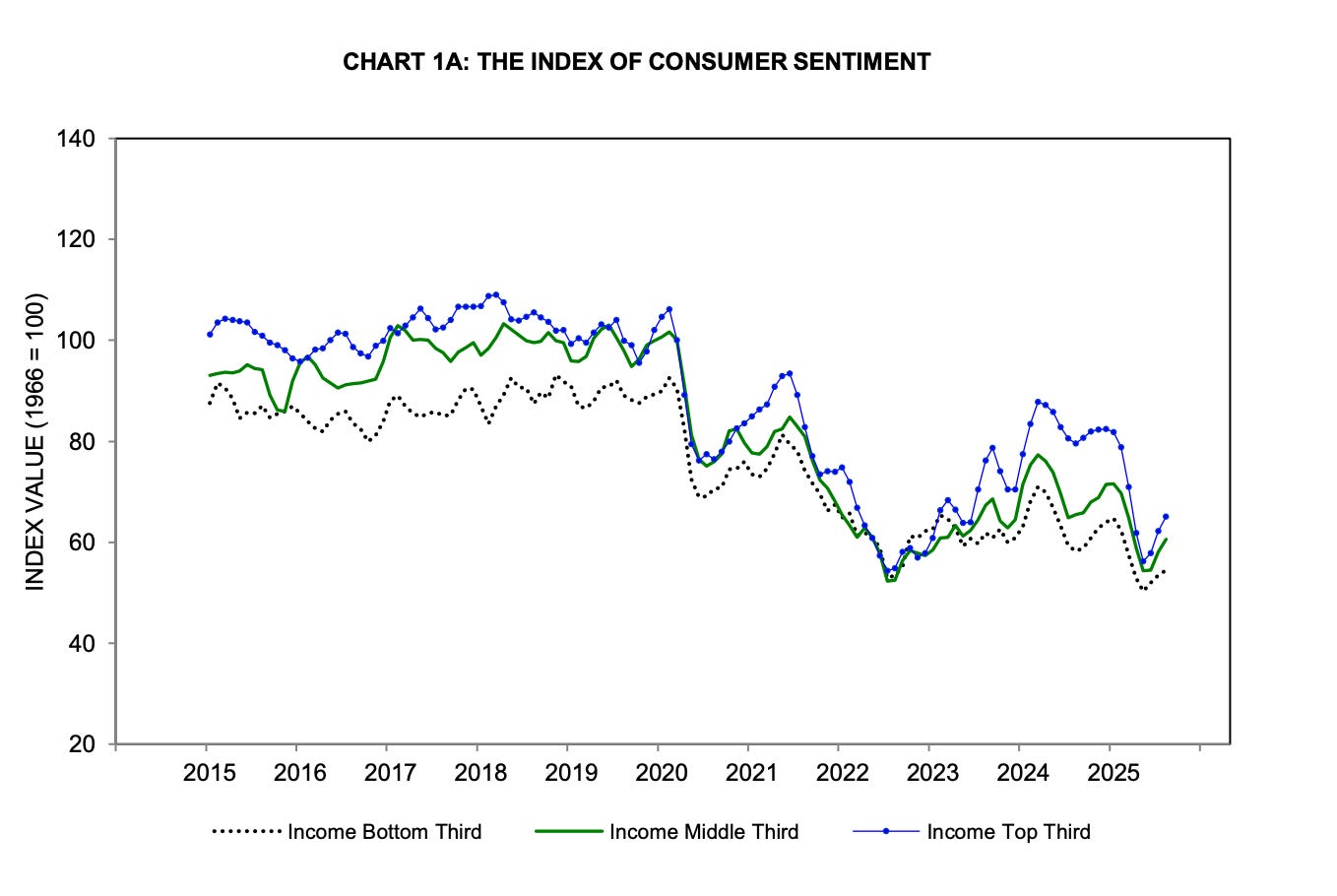

I decided to check out the data for the US to see if I could find the same pattern there. I couldn’t find data at the same level of granularity, but I did find the below chart from the University of Michigan consumer survey. There’s a big dip around the liberation day tariff scare for all income groups, but confidence for the top third of the income spectrum remains much higher than for both the middle and bottom thirds – and that this trend became most pronounced at the start of 2024.

I also found another supporting stat from McKinsey:

“65 percent of high-income consumers plan to spend the same or more compared to last year, while this figure drops to 56 percent for middle-income shoppers and just 48 percent for those in lower-income brackets.”

Looking at both charts, you see a sharp separation in the consumer confidence of wealthier households from that of poorer households at the start of 2024 – a separation that isn’t visible to the same extent at any point in the data going back to 2014.

So, what changed in 2024?

In both the US and the UK, economic growth has been pretty steady since the pandemic, so that’s unlikely to be the issue. Inflation tends to hit poorer households harder – especially the kind of inflation we’ve been seeing of late, which has particularly impacted commodities like food and energy. But inflation rates peaked in both countries in 2022, before falling back to around the central bank target in 2024.

There’s a similar story for unemployment. It’s hard to get real time data, especially since the data is so unreliable thanks to an underfunded statistics body in the UK and the government shut down in the US. But in both countries, unemployment rates have been relatively steady since the pandemic, though they now look to be rising.

My hunch is that the issue is real wages – i.e. the amount someone is paid relative to inflation.

You’re not going to hear much about real wages in the news, becuase economists tend to assume that wages reflect productivity over the long run. They argue that workers’ remuneration reflects the value they add to the production process. In the short run, they think wages fluctuate based on supply of and demand for labour. When unemployment is low and the economy is growing, the assumption is that wages will rise as employers bid to attract scarce workers.

Unsurprisingly, this is not how things work in the real world. If you look at historical data all over the world, the most significant factor that consistently shapes the rate of wage growth is the density of trade union membership (check out this great piece from

for more on this). Employers don’t have to pay workers a wage equal to the value they add to the production process unless employees demand it. In other words, over the medium to long term, the balance of power between capital and labour matters far more in shaping wages than productivity.Scared Workers = Low Wages

Over the short term, supply and demand do clearly matter when determining nominal wages – but only if workers feel confident and powerful relative to their employers. If there’s a scarcity of labour but employees are too scared to ask for a raise or leave their jobs, they won’t be able to take advantage of this scarcity to bid up their wages. Employers certainly aren’t going to offer generous salary increases without this pressure – not at the lower end of the income spectrum, anyway.

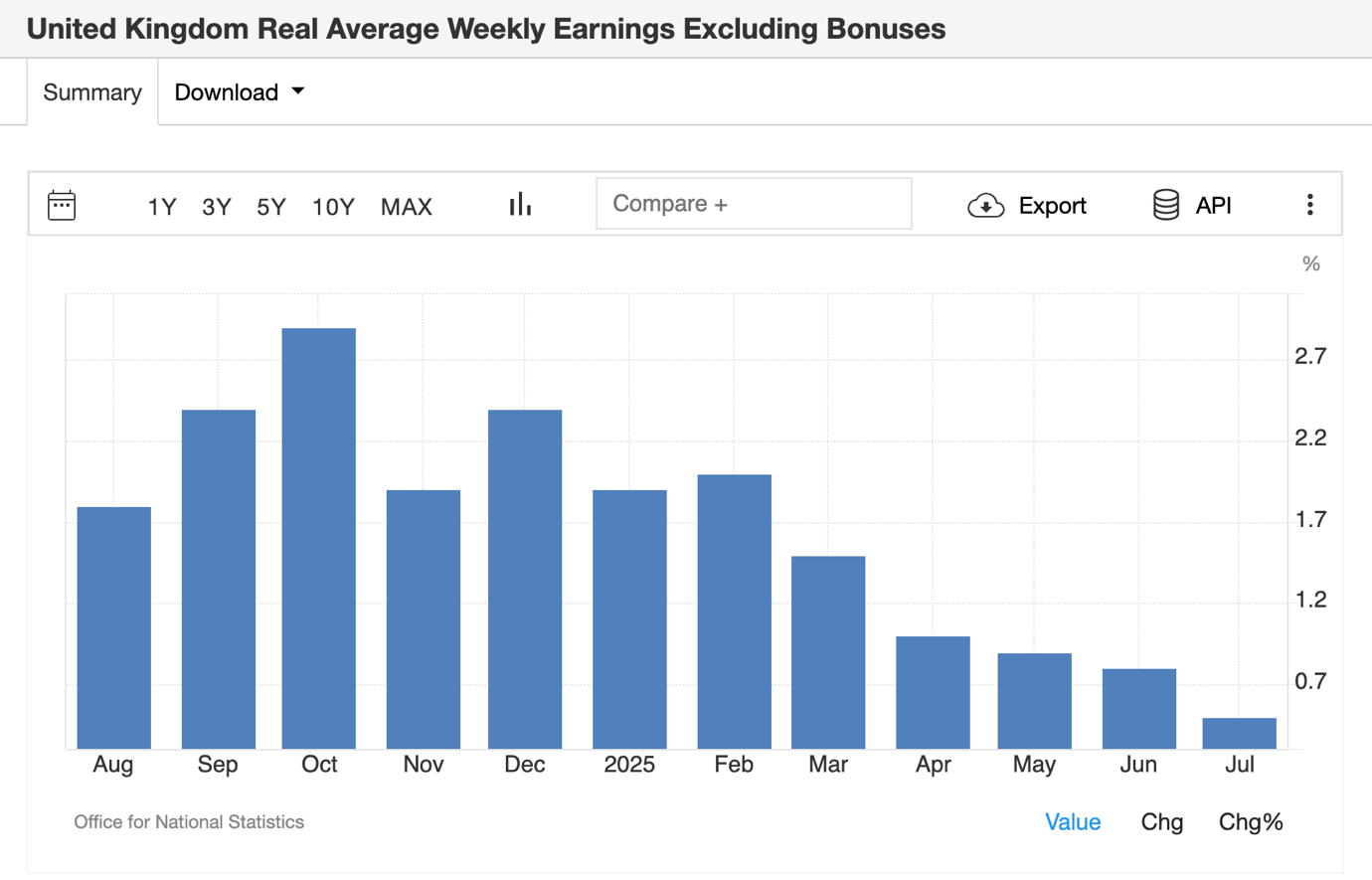

So, you can have a growing economy with high productivity in which workers aren’t being paid their fair share. If you’ve got a stagnant economy, with flat productivity, and high inflation (as we do in the UK), and you’ve got a recipe for falling real incomes – and therefore low consumer confidence. Just look at this chart from Trading Economics of the steady decline in real average weekly earnings over the course of the year.

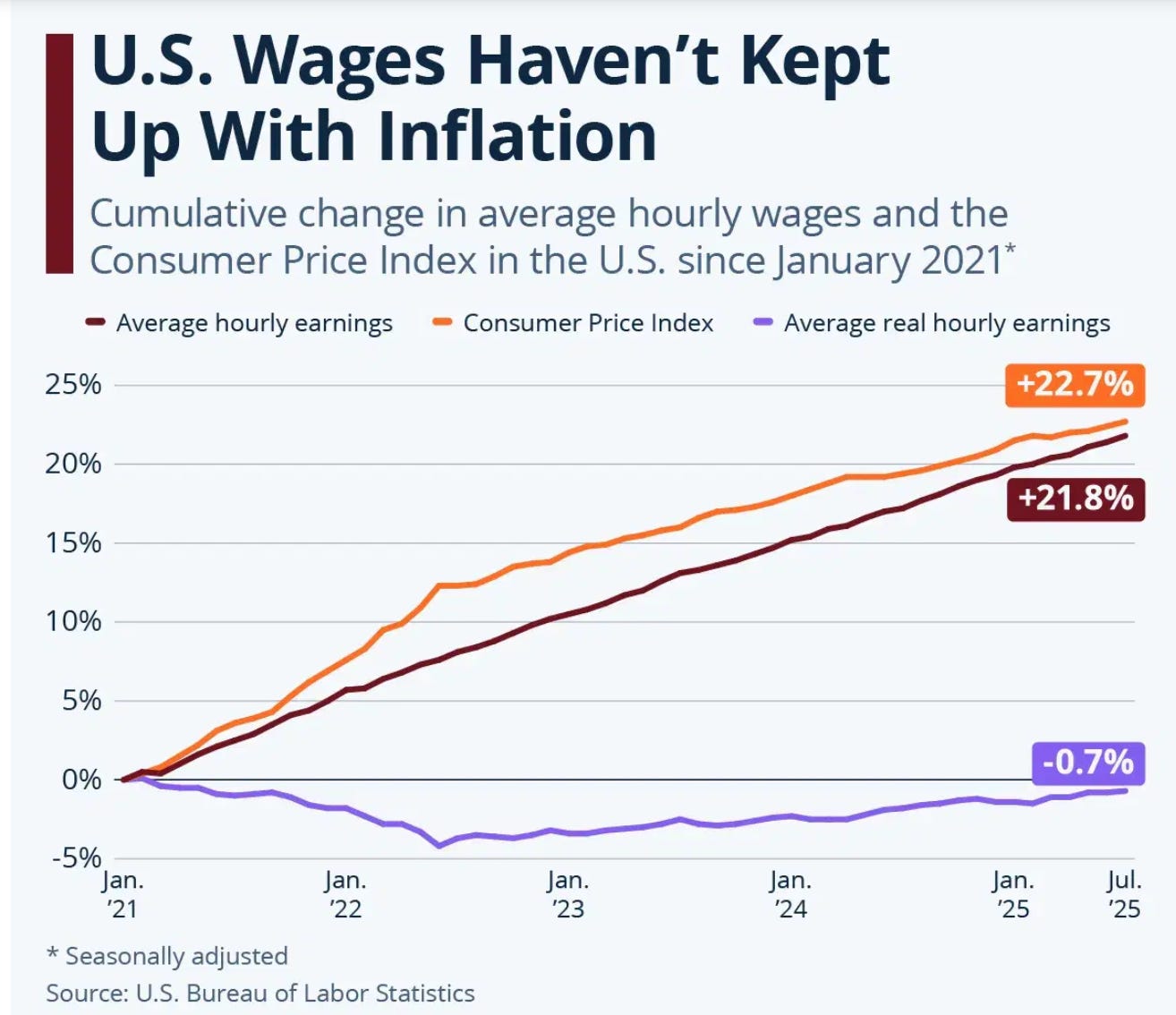

And then check out this chart from the Visual Capitalist, which shows the flatlining of US real wages since the pandemic.

But how does this general stagnation in wages explain the difference between wealthier and poorer households?

Firstly, higher paid workers have more bargaining power relative to their employers. They generally feel more confident in demanding higher wages and are often able to secure these demands. Second, higher paid workers are more likely to own assets. The values of these assets, and the incomes they generate, reflect profit rates across the economy. And when companies aren’t paying workers their fair share, they tend to dish the rest out to shareholders in the form of profits. So, lower incomes for those lower on the income spectrum often translate into more wealth for those at the top.

The End of Optimism

Now, these trends didn’t change sharply in 2024. Most workers saw a significant erosion of their wages over the course of the pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis, which only started to reverse towards the end of 2023. But during the pandemic, there were significant subsidies available for most households, which limited the impact on incomes. In fact, many households were able to build up savings during the pandemic because they couldn’t spend as much. During the cost-of-living crisis, there was again some support for incomes (though not nearly enough). Households supplemented this government support by taking out debt and drawing down their savings, assuming that the economy would soon recover.

But the recovery never came. Instead, at the start of 2024, workers faced the dual shocks of Trump’s tariff war and the sudden threat of AI-induced job losses. Both these trends have made workers fearful for the future. The latest labour market data suggests that workers are increasingly sticking to their current jobs, which is a sure sign that they’re scared for the future – they’re sacrificing potentially higher salaries for job security.

All the uncertainty and volatility in the economy is bad for workers. But it’s great for financial markets. Investors have taken advantage of the market volatility surrounding tariffs to make vast sums of money ‘buying the dip’. And the impact of AI, which is terrifying for many workers, has generated an historic bubble in financial markets that has made some investors very rich.

In short, it’s a great time to be a capitalist and a shitty time to be a worker. If you rely more on wages for your income than wealth, you’re pretty scared for the future. Hence the lower rates of consumer confidence for those lower down the income spectrum. If you rely more on wealth, you’re probably high on the extraordinary gains you’ve seen in your portfolio since 2021.

As I wrote in my piece a few weeks ago, this situation can’t go on forever. Eventually, the bubble is going to burst, investors will see big losses, and unemployment will surge. Governments will probably step in to rescue investors while leaving workers to deal with the consequences of a crisis they played no part in causing. Businesses will use the crash as an excuse to reduce headcount for good. Is it any wonder that the vast majority of people are scared for the future?

It’s why I favour Mutual Equity and employee ownership . There are millions of companies where the founder wants to retire , so let’s use this ‘silver tsunami’ to encourage employee ownership. The workers then become the shareholders.

Great article Grace. I wonder if part of the issue going on here is that underlying the situation in the UK and the US is the relative stagnation/loss of position of these domestic economies within the broader global market. From a distance, it feels like capitalist classes in each nation are engaging in class warfare, in part, to maintain their own relative positions through the further immiseration of their respecting working classes but this is on the back of the neoliberal turn.

It would certainly explain how Australia, in being more directly connected to the Chinese market, is partially shielded (at least for now) from this dynamic.