Who Pays for Inflation?

Inflation is on the up once again. Here’s what it means for workers and bosses.

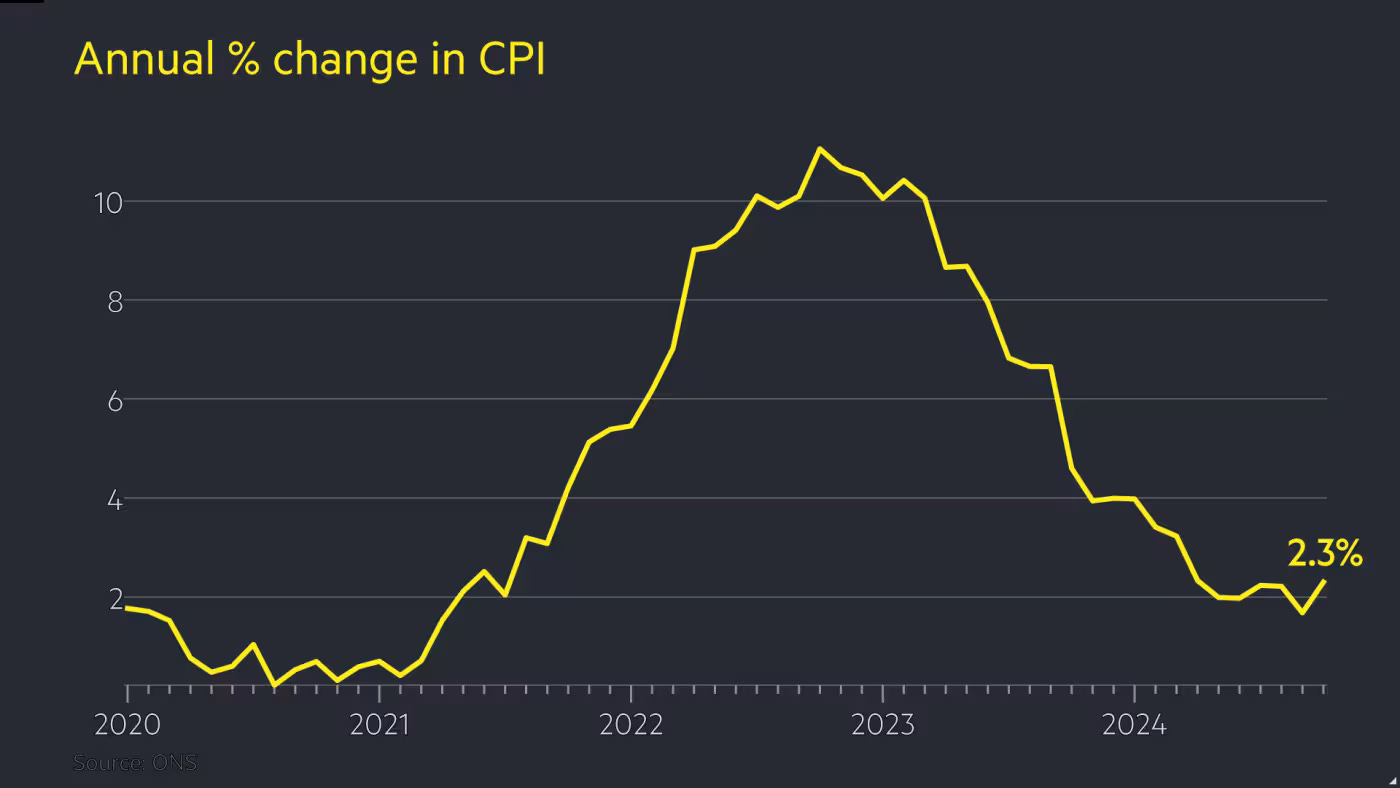

Data out today showed that year on year inflation rose to 2.3% in October, an increase on last month’s 1.7%.

What does that mean?

Year on year inflation is the percentage change in prices from one month of one year to the same month the following year. So, this data release shows that prices have risen by 2.3% between October 2023 and October 2024 – up sharply from last month’s year on year figure of 1.7%.

In other words, prices are rising more quickly now than they were earlier in the year.

Why is inflation up this month?

One of the most significant culprits is rising energy prices. The energy regulator Ofgem recently raised the energy price cap, capping gas prices at 6.44p per kWh, and electricity at 24.50p per kWh.

The annual bill for an average household using both sources of energy will rise by £149 to £1,717. This increase comes after Rachel Reeves announced cuts to pensioner winter fuel payments, potentially driving 100,000 pensioners into poverty.

Will it carry on going up?

Looking into the future, the picture is mixed. On the one hand, energy bills are set to increase again in January. And some have argued that Rachel Reeves’ budget will increase inflation over the medium term.

But food and fuel prices aren’t increasing at anything like the rates they were during the cost of living crisis. And according to the National Institute for Economic and Social Research (NIESR), while the headline rate of inflation has risen, underlying inflation, which excludes the most volatile prices, has fallen.

Over the long term, there are still plenty of potential inflationary risks on the horizon.

Trump’s tariffs may have a significant impact on global supply chains, which could drive up inflation over the next several years. Geopolitical conflict remains an ongoing source of uncertainty when it comes to fossil fuel prices. And climate breakdown threatens to deliver unpredictable inflationary shocks; for example, extreme weather events can destroy crops, raising food prices.

What does higher inflation mean for interest rates?

The Bank of England has a remit to keep inflation below 2%. It does so by setting interest rates, which shape how much it costs to take out new debt. If inflation is too high the Bank raises interest rates, which increases the cost of debt, and discourages businesses from borrowing to invest and households from spending.

With consumer spending and investment down, unemployment is likely to rise. If unemployment is high, bosses will know they can keep salaries low because workers will be too scared to ask for wage increases. This means that workers absorb the costs of higher inflation in the form of lower salaries.

This isn’t a critique of the way central banks try to tackle inflation – it’s just a description of the mechanism through which monetary policy impacts inflation.

So, what’s the critique?

In sum, the way central banks try to control inflation is regressive and anti-democratic.

Let’s take the ‘anti-democratic’ part first. The Bank of England has been ‘independent’ since the 1990s. That means it’s run by a committee of technical experts, insulated from the influence of politicians. The idea behind this change was that it would prevent political leaders from slashing interest rates before elections to make households feel better off.

The problem is that central banks aren’t really independent. Sure, politicians aren’t setting interest rates to try to win elections. But the central bankers who set interest rates are not immune from outside influence – far from it. They’re extremely close to powerful vested interests within business and finance, and these interests are able to wield extensive formal and informal influene over monetary policy.

Workers, on the other hand, are not.

Advocates of central bank independence justify this arrangement by claiming that the setting of interest rates is a purely technical issue, which shouldn’t be the subject of political debate. But monetary policy has massive distributive consequences. Central bankers are making decisions that have significant implications for the distribution of resources across society with no democratic scrutiny.

This is where the ‘regressive’ argument comes in. We know that inflation tends to have a greater impact on poorer households than wealthier ones. This effect is even more pronounced when the price increases are concentrated in sectors like energy and food – as they have been over the last few years. But using interest rates to tackle this problem can make things worse.

First, and most obviously, increasing the cost of borrowing makes highly indebted households worse off. Many poor households are forced to take on debt just to make ends meet by, for example, putting day to day expenses on a credit card. When interest rates increase, the interest payments on this debt can skyrocket, pushing many into severe financial hardship.

Then there are the low-income households with mortgages to pay. Higher interest rates have increased the monthly repayments of some mortgage-holders by hundreds of pounds per month. The Institute for Fiscal Studies found that the increase in mortgage rates has pushed 320,000 people into poverty.

Then there’s the impact on wages and unemployment. The whole idea behind raising interest rates to curb inflation is that doing so slows down the economy. Raising interest rates reduces investment, which slows growth and increases unemployment. When unemployment is high, wages tend to fall. You’re much less likely to ask your boss for a raise, or try to look for a better job, during a recession.

But this fall in bargaining power has a much greater impact on low paid workers than higher paid ones, as the latter tend to have more bargaining power than the former. Some say that’s because high paid, professional workers have unique skillsets that are hard to replace. I’d argue it’s also because they’re generally closer to the people who decide who gets fired.

Why do central bankers target unemployment in this way?

Central bankers can’t shape the world price for important commodities like oil or wheat. But, when the prices of these commodities do rise, they have the power to determine who pays for that increase. And they’re going to make sure that the dominant class is protected from the impact of inflation. Today, that means forcing workers to pay for rising prices in the form of lower real wages to protect profits and rents.

Janet Yellen, former chair of the US central bank, The Federal Reserve, once celebrated unemployment as a ‘worker disciplining device’. The reduction in worker power associated with unemployment makes it easier for central bankers to force workers to bear the costs of higher inflation. Workers aren’t organised enough to bargain for higher wages, so they’re forced to accept higher prices, and the higher interest rates imposed on them by central bankers.

It's the job of central bankers to operate Yellen’s ‘worker disciplining device’. When prices rise, workers have to pay so that capitalists don’t.

The argument isn’t as simple as ‘the capitalist state protects the interests of capital’ – as I explain in my book, Vulture Capitalism, the state is a social relation and policy outcomes tend to reflect the balance of power in society. But, for now, it’s enough to point out that, since the neoliberal revolution of the 1980s, monopoly and finance capital have successfully organised within state institutions to protect their interests. This is why we got central bank ‘independence’ in the first place.

Strongly agree with all you say. Our economic system has been designed by the richest people and their henchmen to benefit - you guessed it - rich people! Inflation doesn't hurt people without savings, as long as their incomes keep pace. Inflation helps those in debt as it shrinks the size of that debt, as long as interest rates aren't raised. Inflation does hurt those with savings, but then they have savings. Who should/can bear the cost of inflation - those with money or those who are in debt?

Also, raising interest rates artificially and temporarily raises the value of the currency, making imports cheaper and exports more expensive, putting that Country's workers out of work, increasing the trade deficit and reducing the demand for currency which reduces its value again - it's a downward spiral for an economy. I know many MMT economists think trade balances don't matter the majority of the electorate do, at a very pragmatic day-to-day experience level, and people like Trump play to it with talk of protecting jobs and income levels with tariffs. What is the MMT response?

Here in Australia, there is an attempt to abolish a never-used power which the Treasurer has to overrule the Reserve Banks decisions on interest rates, which attemp to keep inflation within a 2-3% range, so higher than the UK's 2% target. I hope it fails.

Inflation here is currently 2.8%, but the Reserve Bank is delaying cutting, claiming it is concerned about underlying inflation. The Albanese Government obviously wants rates falling before the federal elections, likely in March.

Trump's tariffs are unlikely to have much effect on Australia as we are more closely tied to China and Asia rather than the USA, which has a trade surplus with Australia, mainly in investment rather than products.

If Trump slashes the Inflation Reduction Act, which involves investing $80b in American renewables, then Prime Minister Albanese last week invited investors to bring their funds to Australia, so America's loss could be our gain. American workers would lose jobs, but we would gain them.

As for energy, we are experiencing a boom in investment in renewable energy, particularly solar, wind, hydro and increasingly batteries, which should enhance our national security by making us more energy independent. We just need more EVs to cut oil imports.

Workers pay for inflation, just as American workers will pay for Trump's tariffs in higher prices for consumer goods, raising inflation and requiring higher interest rates.

Yet Americans voted for Trump, voting to raise their own cost of living by imposing a tariff, like a sales tax, on themselves, to be collected by the US Government. A vote for Trump was a vote for higher taxes. Crazy!

Australia, which recently won a trade war which China tried to start with us, but failed, prefers free trade, which lowers the prices of products in shops. Consumers win, and our government has a surplus.

American politics is weird, just like Trump, as Walz correctly said.