The Squeezed Winners

Britain’s middle-earning graduates did everything right - but they're not receiving the rewards they were promised.

In the rich world, capitalism has functioned according to an implicit bargain: work hard, keep your head down, and you’ll have a better life than your parents. You may not become rich, but you’ll be secure. And whatever your frustrations, the basic structure of society will appear tolerable because things seem to be getting better.

Student loans were folded into that settlement. They were sold as an investment: a short-term expense in exchange for a long-term payoff. University would open the doors to professional careers, higher wages, and stable housing. The repayments would feel manageable because the graduate premium would comfortably exceed the cost.

Today, that promise is collapsing. And the impact is being felt most acutely by those middle earners who were once the most reliable supporters of the status quo.

When education doesn’t pay

Under Plan 2 loans, graduates repay 9% of earnings above the threshold, which currently stands at £28,470. But this stacks on top of income tax, national insurance, frozen thresholds and high rents. For many young professionals, the effective marginal tax rate now approaches – and sometimes exceeds – 50%.

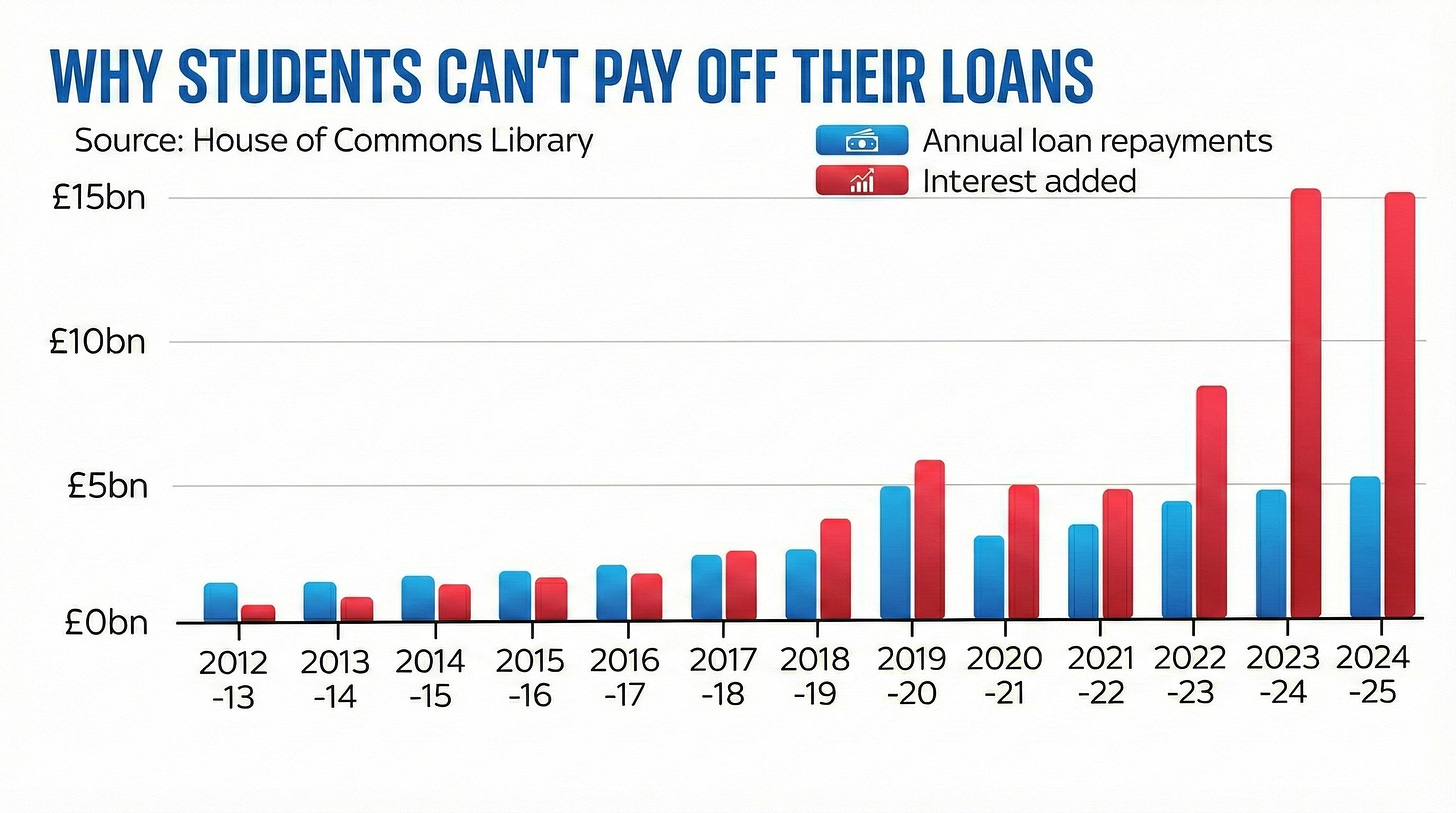

Most lower earners do not repay the loan in its entirety - some never hit the threshold at which they must start repaying the loan. And high earners pay it off quickly, which means they’re paying less interest and the loan ends up relatively cheap. It’s middle earning professionals who end up getting squeezed - they’re earning enough to repay their loans, but not enough to repay them quickly.

When interest rates were very low, this effect wasn’t so pronounced. But as they’ve risen over the last few years, the gap between those repaying their loans early and those repaying them late has increased.

The worst affected are those pursuing a career which requires a university degree, but which only provides a moderate income - think teachers, engineers, nurses, civil servants. In other words, the mid-career professionals earning £40–70k – historically the backbone of political stability.

This group would once have expected to graduate into a stable, professional job, which provided opportunities for advancement and salary increases throughout their twenties. By 30, they’d be able to secure a mortgage, which they’d pay off in a decade or so, retiring comfortably in their early sixties.

Today, they’re graduating into a chaotic job market with high competition for entry level roles. If they do secure a job, their starting salary will only just allow them to cover their rent, bills, and other expenses. Opportunities for advancement and salary increases will be far more limited. If they manage to buy a home in their thirties, they’ll likely be repaying their mortgage into their sixties. And few will be able to save enough for a comfortable retirement.

To add insult to injury, this group now faces student loan repayments that act like a permanent earnings surcharge. For many, the balance will never be cleared. They are paying for access to a labour market that no longer delivers the reward the payment was meant to finance.

A crisis of legitimacy

Public debates about student loans usually revolve around whether these loans are fair. Many maintain that graduates should have to pay the price of entry to university, as they earn more on average than non-graduates. Sympathy is limited – understandably so – among workers without degrees facing stagnant wages.

But the issue is less fairness than legitimacy. Those middle earning professionals are the bedrock of support for our economic model. If they withdraw that support, as they are now, the potential for a radical break with the current system increases. After all, why should they continue to support an economic system that offers them only stagnation, insecurity, and decline?

Student loans are a big part of this calculation. A graduate paying 9% extra tax for 30 years, unable to buy a home until their late 30s, all while watching asset-owners accumulate wealth effortlessly, does not interpret their situation as a fair exchange between effort and reward.

And they’re unlikely to simply sit down, shut up, and accept their lot. This group has both political voice and expectations of influence. When they get angry, they rarely withdraw quietly.

From moderates to radicals

Historically, middle earners moderated politics. They resisted radical redistribution because they believed they would be the future beneficiaries of growth. If hard work reliably improved their lives, systemic change seemed unnecessary and risky.

But today, that calculation is changing. When living standards plateau for a generation, even for those with good degrees and professional jobs, most people start questioning whether the system really works in their interests.

Of course, a radical break with the status quo will not necessarily benefit the left. It could also end up benefitting the far right. Perhaps the most important factor determining which way the scales tip is how the middle classes understand themselves and their relationships to one another.

Neoliberal politicians sought to create a world in which middle class households saw themselves as individual economic units in constant competition with one another. Such an outlook militates against collective solutions to collective problems and predisposes one towards conservativism.

In an individualistic society, people often blame themselves when their economic situation deteriorates. This self-blame metastasizes into an inchoate rage, which is often directed towards convenient scapegoats. After all, it’s far easier to respond to feelings of powerlessness and despair by attacking the migrant worker who lives on your road than the billionaire who owns your company and just cut your wages.

But individualism is not set in stone. In fact, it is a relatively recent phenomenon. Before the 1980s, our society was much more collectivist – people were more likely to see themselves as interdependent and were therefore more likely work together to solve their collective problems.

Reviving this spirit of collectivism would radically transform the political implications of this moment. We could begin to imagine collective solutions to our social problems, rather than blaming ourselves – and others – for the failure of the system. Instead of tax cuts for the rich combined with culture wars, we could have housing reform, public investment, stronger workers’ rights, and public ownership of critical physical and social infrastructure.

The end of the bargain

The student loans crisis is a sign of the economic times. A deep rift is emerging between what people expected their lives to look like, and the reality of living and working in a stagnating economy.

The graduate surcharge is politically potent because it links a systemic failure to individual biographies. Every payslip becomes a reminder that effort does not guarantee advancement. And once enough people reach that conclusion, belief in the social contract begins to break down.

When the people who were meant to inherit stability instead inherit permanent stagnation, they do not simply feel poorer. They feel misled. What follows depends upon how that feeling is interpreted – as a personal failure, or a systemic one.

Great article. I think whether this class breaks left or far right depends on how we organise. As long as the left is materially captured by the neoliberal left the far right has the advantage of appearing to offer the more radical break.

We need to educate, agitate and organise to win a renewed a commons.

Yes, the well-known trap of a system that functions precisely by exploiting the majority of individuals, who ultimately "fail," only to then shift the blame for that "failure" onto the individuals themselves. Precisely for this reason, it remains important to maintain and increasingly disseminate the capacity to analyze capitalist society, a skill that has its cornerstones in the "classic" authors. Possessing the right tools for analyzing and criticizing capitalist society allows us to better understand who the true enemies are and fight them more effectively. The challenge in this historical period is precisely to spread this awareness as widely as possible; a difficult task, but one worth working toward every day to build a more just and supportive world.